The Forgotten Moral Function of Reason

Authentic reason as an existential commitment to truth is about more than logic and problem-solving. It is a moral commitment to the collective pursuit of authenticity and freedom; a form of loving.

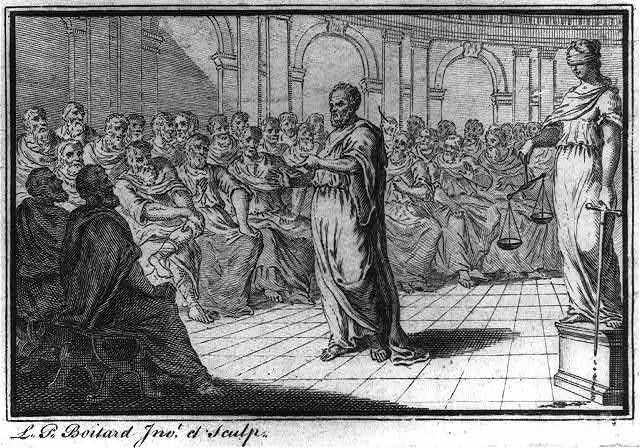

(This is a slightly edited version of the essay I read in my dialogue with Adam Robbert and Jacob Given on their “Disputations” series on Substack live. “Disputations” is a structured dialogue series inspired by the medieval disputatio, meant to create a formalized method of dialogue and exchange.)

What Does it Mean to Reason?

What does it mean to reason? Most people associate reason with thinking and problem solving. If I tell you to think about someone who is good at reasoning, chances are you will think of a famous scientist, mathematician, or philosopher; someone who spends a lot of time thinking and has a special sort of insight into some specific facet of reality. We say that one’s belief is legitimate if one can provide good reasons to justify their belief. When we search for the reasons why something happened, we are attempting to provide a logical explanation for the causes that led to a certain event. Reason, when effectively utilized, should give us clearer vision of reality and help us better navigate life.

This is all well and fine, but I want to give you good reasons to believe that this doesn’t tell the whole story about what reason is in its most profound sense. I am going to make the case that the commonplace idea of reasoning I’ve just discussed only tells part of the story of what it means to reason. The limitation of reason to problem solving and logical thought is an impoverished idea of reason that I will call “instrumental reasoning,” which is largely a result of the modern schism between science and values, ontology and ethics, and exacerbated by hyper-specialization in academia and the fragmentation of the pursuit of truth into isolated academic disciplines.

What I would like to recover here is the moral nature of reason that is completely omitted in our commonplace idea of instrumental reason. I say recover because the idea that the cultivation of reason is inherently ethical is an ancient one, and I am thinking here specifically of Plato, for whom a life committed to the pursuit of truth and the love of wisdom necessarily entailed the cultivation of virtue and the purification of desire in pursuit of the highest Good; a pursuit that inevitably transformed the being of the devoted philosopher. Thus, I will argue for a conception of reason that accounts for instrumental reason while moving beyond it. I believe that authentic reason does not limit itself to disciplinary boundaries, but aims at knowledge of the Absolute through the attempt to synthesize knowledge of disparate disciplines by exploring how they cohere with each other in reality. Authentic reason aims at a disinterested knowledge of the Whole and seeks to understand one’s place in it.

Reasoning at its best leaves the prejudices of the self behind for the sake of attaining a just and truthful vision of its object. Authentic reasoning involves a movement away from the ego towards reality itself; the development of a self-forgetting and genuine concern for seeing someone or something as they really are. In this way, authentic reasoning transforms the knower herself, making her more capable of a just perception of reality, a movement which is synonymous with loving, and which inevitably changes how the knower participates in and relates to reality.

Recovering Philosophy as a Way of Life

Towards the end of Philosophy as a Way of Life, Pierre Hadot ponders whether the transformation of one’s being and perception aimed at by philosophers in antiquity is still possible in an age dominated by the quantitative universe of modern science. Philosophy as a way of life in antiquity had as its ultimate goal the figure of the “sage,” the personification of wisdom; a person who has cultivated virtue, peace of mind, and knowledge of oneself and their place in the cosmos to the highest degree.

Hadot argues that philosophy as a way of life began to give way to academic philosophy in the medieval university, where philosophy became a handmaiden to theology, and was not meant to educate well-rounded human beings but to train professional scholars who would train other scholars. Philosophy since then has remained a largely academic enterprise limited to the university, and the challenge of pursuing philosophy as a way of life has been accentuated by the dominance of modern science’s quantitative view of reality which, as Hadot points out, is radically different from the world of human perception, saturated as it is by existential significance.

Hadot argues that while science and its technical applications do indeed transform certain aspects of daily life, “it is essential to realize that our way of perceiving the world in everyday life is not radically affected by scientific conceptions. For all of us—even for the astronomer, when he goes home at night—the sun rises and sets, and the earth is immobile.” Hadot sets up a distinction here between the world of science and the world of perception. For the world of science, the Earth is an impersonal object of observation that spins around an axis and rotates around the sun. In the world of perception, the Earth seems immobile and provides the ground and possibility for all life and meaning. What Hadot is implying here is certainly not a form of anti-intellectualism or science-denial. Rather, it is a call to the phenomenological insight that all knowledge implies consciousness of knowledge; that the world of science presupposes and is built on the world of perception, and can therefore not dismiss the world of perception without undermining itself.

This is an important move that Hadot makes towards the project of recovering philosophy as a way of life. The normativity of values and truth that is characteristic of the world of perception is foreign to the quantitative universe of scientific materialism, which smuggles in ideals of rationality and truth while at the same time disavowing normativity by reducing reality to its quantitative aspects, thereby eliminating normativity altogether. Hadot argues that:

“[t]he quantitative universe of modern science is totally unrepresentable, and within it the individual feels isolated and lost. Today, nature is nothing more for us than man’s “environment”; she has become a purely human problem, a problem of industrial hygiene. The idea of universal reason no longer makes much sense.”

I will return later to the meaning of universal reason, but for now the important point is that recovering philosophy as a way of life requires that we resist the reductive and totalizing tendency of instrumental reason by returning to the life-world of our lived perception. Hadot argues that we can do this by attempting a shift from a utilitarian (or scientific) perception of the world to an aesthetic one, and he claims that we find this kind of distinction in the work of Henri Bergson.

Bergson on Perception and Intuition

Utilitarian perception is associated with an instrumental form of reasoning which is a trademark of modern science. Bergson saw utilitarian perception as a kind of default mode of human awareness which he called “intelligence,” which we find most highly developed in the human species and is most clearly exemplified in modern science and technology. Intelligence for Bergson has not evolved primarily for thinking or theorizing, but for action. The intellect is directed towards practical utility and aims at the manipulation of one’s environment through the use of inorganic instruments. Cognitively, intelligence works by identifying stable patterns within the flux of one’s environment and translates these into static concepts that we can manipulate in thought, as we do in speech or in mathematics.

The important point here for Hadot is that the utilitarian perception of the intellect, our default mode of perception, is instrumental in that it looks at objects in the world as means to vital ends; it looks at things and asks “what can it do for me?” The knowledge aimed at by utilitarian perception is thus relative and self-interested, since it is bound up with the vital needs of the organism and the urgency of action. Intelligence is primarily concerned with producing knowledge that yields the power to control and manipulate the object of its concern. When utilitarian perception projects itself onto the totality, we end up with the quantitative universe of modern science.

The transition to an aesthetic form of perception occurs when our attention to the world becomes disinterested, a form of awareness that Hadot and Bergson associate with artists. Hadot quotes Bergson’s description of aesthetic perception extensively:

“When [artists] look at a thing, they see it for itself, and no longer for them. They no longer perceive merely for the sake of action: they perceive for the sake of perceiving; that is, for no reason, for the pure pleasure of it… That which nature does once in a long while, out of distraction, for a few privileged people, might not philosophy… attempt the same thing, in another sense and in another way, for everybody? Might not the role of philosophy be to bring us to a more complete perception of reality, by means of a kind of displacement of our attention?”

The displacement of our attention from a utilitarian to an aesthetic perception implies a phenomenological turn towards what Bergson would call intuition. The difference between Bergsonian intuition and phenomenology could be a paper of its own, but for our sake I will use these terms synonymously to refer to aesthetic perception, which aims at a more complete understanding of reality through a disinterested mode of awareness.

Bergson defined intuition as “the intellectual sympathy by which one is transported into the interior of an object in order to coincide with what there is unique and consequently inexpressible in it” (Introduction to Metaphysics). Whereas intelligence arrests movement and produces knowledge of its object by reconstructing it with generic concepts, yielding relative knowledge of an object by defining it by what it is not, intuition implies a direct sympathy between the knower and the known through a direct contact of the knower with the vital movements and individuality of the known.

Bergson associates intelligence with analysis, which moves from concepts to reality, while intuition moves from reality to concepts. Analysis attempts to grasp phenomena by breaking them down into their most elemental parts and recomposing them through the use of ready-made concepts, whereas intuition attempts to free itself from the artificial constraints of language to achieve a non-conceptual sympathy between one’s being and the phenomenon in question. It’s the difference between studying sheet music and breaking down a melody into its individual notes and chords, analyzing the time signatures and frequencies, versus closing your eyes and letting the melody overwhelm you, take control of your body and inhabit your being in a way that blurs the boundaries between yourself and the music.

Freed from our concern with matter and the demands of action, Bergson believed we could open ourselves up to experiencing facets of the world that remain obscured by utilitarian perception and self-interest. Furthermore, the phenomenological turn also directs our attention towards the fundamental structures of conscious experience, such as the intentionality of consciousness and the pre-reflective unity of perception that make it possible for the world to appear meaningful to us in the first place. Thus, when intuitive knowledge supplements the knowledge yielded by utilitarian perception, Bergson believed we end up with a more complete perception of reality.

Bergson’s metaphysical description of the turn from instrumental to aesthetic perception is theoretically solid and compelling, but he isn’t very forthcoming about the practical details about what this transition actually looks like in practice—at least not in his metaphysical writings. However, we do get a better idea of what the connection is between intuition, reason, and morality in The Two Sources of Morality and Religion.

Bergson's Moral Philosophy

There, Bergson argues that the pinnacle of moral life is mystical experience translated into action. The perennial teaching of the mystic is one of universal love, that we should love our neighbor as ourselves. Bergson considers this to be a genuinely new development in the evolution of life. Whereas he considers the original source of morality in human society to be akin to the instinctive force that maintains the social coherence and tribalism of animal societies, the second and novel source of morality is a human creation born from intuition.

This intuition is a creative emotion that impels the mystic to pursue the impossible vision of a universal fellowship of humanity, which is perhaps most clearly expressed in the universal declaration of human rights. The mystic for Bergson thus exemplifies the highest degree of intuition and direct intellectual sympathy with reality.

It should be noted that for Bergson, however, intuition guides reason and not the other way around. The moral aspiration generated by the experience of mystical love is rationalized by reason after the fact. Reason does not deduce this love on its own accord, but attempts to bring the light of language to this ultimately ineffable experience in hopes of inspiring this same love in others. Authentic reason, which I will define below, thus has its magnetic center beyond itself. That center has historically been given name of the Good, God, the One, the Absolute, or the Comprehensive, among many others. Bergson called it the élan vital, the vital impetus behind the evolution of life, which for him was synonymous with God.

When Bergson’s ideas are combined with Karl Jaspers’ conception of authentic reason, we can see how authentic reasoning is a form of love that is decreative in Simone Weil’s sense of the word, in that the love of truth for its own sake constrains the possessive and instrumentalizing tendencies of the ego and commits one to the liberatory task of allowing others and the world to flourish and appear in their authentic individuality.

Karl Jaspers on Authentic Reason and Anti-Reason

What I am calling “authentic reasoning” is an existential commitment to the pursuit of truth for its own sake; a decreative process undertaken for the sake of clearer vision of reality. Indeed, the desire for truth is in equal measure a desire for justice, in that we desire that our reasoning measure up and do justice to the truth that confronts us.

Even those who employ reason for morally contemptible projects must attain to some truth at the end of their process of reasoning to effectively pursue their Machiavellian ends. However, reason’s aspiration for truth cannot find the full actualization of its nature in the Machiavellian person, where the pursuit of truth is constrained by narcissism and selfish desire. This is an extreme example of what makes instrumental reason inauthentic in an existential sense, in that truth is only desired insofar as it serves the interests of the individual. Here, reason and the desire for truth end at the boundary where the ego meets the Other.

As Karl Jaspers notes in Reason and Anti-Reason in our Time, authentic reasoning is self-forgetting and wants to liberate truth in the world, so that others and oneself can pursue truth in loving struggle and express the fullness of their being in the light of day with responsibility, that is, in a way that does not interfere with the freedom of others to do the same. This is what Jaspers expressed when he wrote that

“man’s independence is only possible when man’s will to power has ceased to exist, and perhaps only in a state of powerlessness. Powerlessness seems the condition for acting in real freedom and for arousing freedom in others. In selfless humility, bereft of selfwill, the individual has a chance to take a minimal part in helping to create an atmosphere in which truth can thrive.”

Furthermore, for Jaspers authentic reason aims at the Absolute; it is not satisfied with rigid disciplinary boundaries and desires a synthesis of disparate disciplines that approach reality as it actually is: a continuous and coherent whole. The sharp separation between physics, biology, neuroscience, and consciousness, for example, exists only in the university; it does not reflect how these domains of reality seamlessly cohere in nature. For Jaspers, it is precisely “the wholesale departmentalization of current thinking in a mass of specialized disciplines and the collapse of the breadth of Reason into mere intellectualism” that has led to the all-too-common forgetting of the moral nature of reason. In opposition to the mass departmentalization of thinking and the associated instrumentalization of reason, authentic reason “keeps the way open to the Comprehensive, deepens every bond by illuminating it, [and] secures the continuity of existence.”

Indeed, Jaspers notes that “[i]n order to seek the One, the seeker himself must become one.” Authentic reason’s pursuit of the Absolute demands the unity of the self; only when our life and character are aligned with the selfless desire for truth can reason fulfill its highest aim.

It should be briefly noted here that Jaspers contrasted authentic reason with anti-reason, a term he used to describe the thoughtlessness and moral blindness he witnessed in Nazi Germany, characterized by a relinquishing of the self’s responsibility to truth in favor of conformity, ideology, and an intoxicating mob mentality.

Bergson’s description of the shift away from utilitarian perception towards intuition parallels Jaspers’ progressive account of authentic reason in that both saw the desire for truth as an expression of the individual’s desire to reunite with the Absolute, like a wave falling back into the ocean, and that this return cannot be attained without a simultaneous moral transformation of one’s being and perception.

Reason is the intellectual faculty which discloses reality through rational thought. It expresses our desire for truth. What Bergson and Jaspers show is that this desire reaches beyond our practical vital needs towards foundational questions about the fundamental nature of reality and one's place in it. This marks reason's inward turn, expressed in the admonition to “know thyself.” Authentic reason pushes ever deeper into knowledge of oneself in hopes of finding the Absolute. Although Bergson is correct that this kind of knowledge is not something that can be discovered by reason alone, Jaspers’ contribution here is in making explicit that this movement of spirit towards the Absolute is what serves as reason's north star and compels its questioning. However, as I have been alluding to, progress towards this end requires a moral transformation on the part of the philosopher.

Simone Weil and Iris Murdoch on Decreation

I think this transformation is best captured by Simone Weil’s concept of “decreation.” Decreation for Weil is an inherently theological concept where one replicates God’s act of creation, where God creates the world by becoming less than what God actually is to make room for creation. Weil argued that we can replicate this ultimate act of love by relinquishing mundane attachments and dissolving the ego through the cultivation of a radical and loving attention to life that demands nothing in return. The emptiness left by the diminished ego makes room for deeper insight into reality.

However, we need not necessarily assume the existence of God to accept the profundity of Weil’s thought. Iris Murdoch synthesizes decreation from a secular point of view when she writes that “[m]oral philosophy is properly… the discussion of this ego and of the techniques (if any) for its defeat” (The Sovereignty of Good). Furthermore, this process entails that “we cease to be in order to attend to the existence of something else, a natural object, a person in need.” And finally, that the ability to perceive reality “is a kind of intellectual ability to perceive what is true, which is automatically at the same time a suppression of self,” meaning that the epistemic virtue of exhibiting facts is bound up with the moral virtues of humility and self-effacement.

For Murdoch, the epistemic function of reason is inseparable from reason’s ethical function and desire to know the Good. She follows Plato in arguing that technē (the practical knowledge associated with arts and crafts such as medicine, farming, or carpentry) can serve as an entry and training for moral life. Mastery of any particular technē engages the practitioner in a process of learning that demands humility and close attention to something beyond the self—virtues that are easily translated into moral life. Instrumental reason is thus a limiting case of authentic reason stripped of its moral valence, where the connection that Plato identifies between technē and the cultivation of virtue is severed.

Authentic Reason is a Form of Love

It is no surprise that we have ended up here with an image of authentic reasoning as a form of loving akin to that found in Plato’s Symposium. There, the soul’s yearning for truth stokes its desire for the Beautiful, not anything beautiful in particular, but true Beauty; the essence of Beauty itself, a process that is only accomplished by the sublimation of desire and purification of the will for the sake of truth. This process is philosophy itself, a life devoted to the cultivation of reason and the desire for truth for its own sake. This love is decreative, in that it wants to sacrifice the soul’s attachment to the ego so that truth may shine forth.

In the end it’s all really quite simple. As Maya Angelou elegantly put it, “Love liberates. It doesn’t just hold—that’s ego.” Reason flourishes and is most fully actualized in the lover of wisdom that commits to the pursuit and liberation of truth for its own sake. The lover must become worthy of the beloved.

I leave you with a quote from José Ortega y Gasset in What is Philosophy? that I always return to, and which beautifully conveys the thought that I have attempted to unfold here:

“But that – to seek in a thing what it has of the absolute and to cut off all other partial interest of my own toward it, to cease to make use of it, to cease to wish that it serve me, but to serve it myself as an impartial eye so that it may see itself and find itself and be its very own self and for itself – this – this – is this not love? Then is contemplation, at root, an act of love, in that in loving, as differentiated from desiring, we are trying to live from within the other and we un-live ourselves for the sake of the other?”

Great post! I enjoyed your synthesis of these amazing thinkers.